“What does peace mean to you?”

This is a question I was asked multiple times over the course of the 2020 Peace Summit for Emerging Leaders in Bangkok, Thailand.

I had a really clear idea of what peace meant to me when applying to attend (I’ll expand on this later), based on my own activism and advocacy work in Canada and the Philippines. I was attending the conference in hopes of learning about practical peacebuilding tools, but I was surprised to see my definition of peace had both expanded and deepened over the course of the summit.

· · ·

Turning Inwards to Break Cycles of Trauma and Violence

One theme that was present throughout the Summit was finding peace within yourself. As someone who often seeks practical, tangible, systemic and policy-focused approaches, I nearly dismissed this as a ‘feel-good’ emotional appeal. Well, yes, personal healing is good, I thought to myself, but what does any of this have to do with peacebuilding?

Then I realized that inner peace is so you don’t externalize the violence you yourself experienced. One speaker shared the following quote: “If we do not transform our pain, we’ll most surely transmit it.”

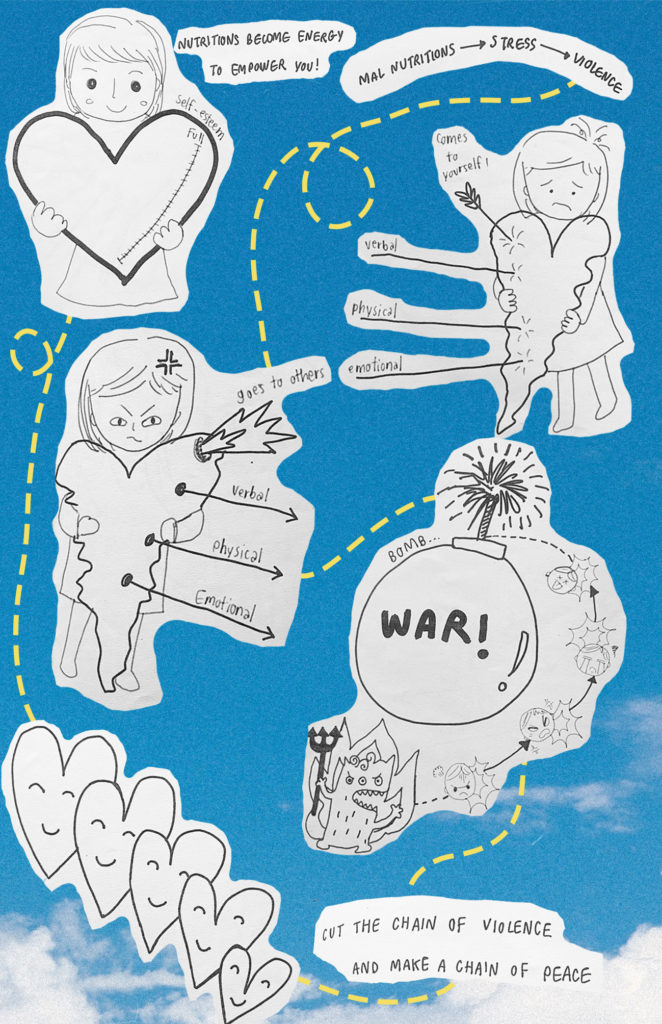

It’s about breaking cycles of intergenerational trauma and violence, and it’s really important. Many of the summit sessions brought to mind a workbook (see snippets in the image on the left) that my colleague at the YWCA of Thailand showed me earlier that week. She had translated the book originally from a Peace Camp by YWCA Osaka. The book takes you through a self check-in process where you take stock of how you’re feeling, what your body and mind need to feel nourished, who your supporters are and what’s important to you. It seems basic, but it’s an exercise I doubt many of us do often (or ever, for that matter). We’re usually taught to ignore the signals our body sends us, and keep working, or doing what’s expected of us at the expense of our wellbeing.

· · ·

Systemic Limitations of Inner Peace

There’s a major caveat to inwards reflection, however. The inner peace narrative can dangerously feed into the idea that ‘we’re all human’ and ‘all experience pain and suffering’ and we are thus equal. But we know there are factors that put people from marginalized communities at higher risk of experiencing violence, that make it harder to escape violence, that make it harder to seek support.

What we actually need is to talk about inner peace and structural oppression all in the same breath. The burden of finding or making peace cannot and should not fall on the individual, especially if that individual experiences intersecting forms of marginalization or lacks a robust support system. What if you cannot find peace because you experience ongoing violence? And when I say violence, I don’t mean just the direct, physical kind – I mean structural violence, where social systems or institutions harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs.

Considering the experiences of many women, transwomen, nonbinary, and Two-Spirit people:

- How can you find peace when you are burdened with caring for your children, families, and communities? (and this burden only becomes heavier in times of crisis or war?)

- How can we find peace within if we experience violence in our homes? (the number one perpetrators of violence against women are their intimate partners)

- How can you ‘look past’ housing insecurity and homelessness?

- When your ancestral lands are being violently occupied and destroyed?

- While precariously employed and one emergency away from not being able to pay for groceries? (the majority of part-time workers in Canada are women)

- When you can’t ever walk on the street alone without fearing for your life?

The comments of Dr. Jamar Jabr, head of Palestine’s mental health services, on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a Western concept perfectly sums up my point:

PTSD better describes the experiences of an American soldier who goes to Iraq to bomb and go back to the safety of the United States. He’s having nightmares and fears related to the battlefield and his fears are [based on a threat that’s no longer there]. Whereas for a Palestinian in Gaza whose home was bombarded, the threat of having another bombardment is a very real one. It’s not imaginary. There is no ‘post’ because the trauma is repetitive and ongoing and continuous.

Even if I show empathy and compassion toward others, even if I regularly see a therapist, even if I’m in touch with my body and emotions… in the face of constant oppression and a lack of human rights, I cannot experience peace in the actual sense.

In Jabr’s words, “What is sick, the context or the person?”

While, yes, it’s admirable if you can develop resilience, but imagine if you didn’t have so much to be resilient for. Imagine if you didn’t have to defend your lands from exploitation and degradation. And you were guaranteed a safe and adequate home to return to each night. And you lived free from violence and criminalization. And you belonged to numerous healthy and vibrant communities that could support you and vice versa.

Mental health or inner peace do not exist in a vacuum. That’s why, at YWCA Canada, we advocate for intersecting issues such as gender-based violence, housing, economic equality, and we do it from an intersectional feminist lens.

· · ·

Looking at the root causes of violence

“What does peace mean to you?”

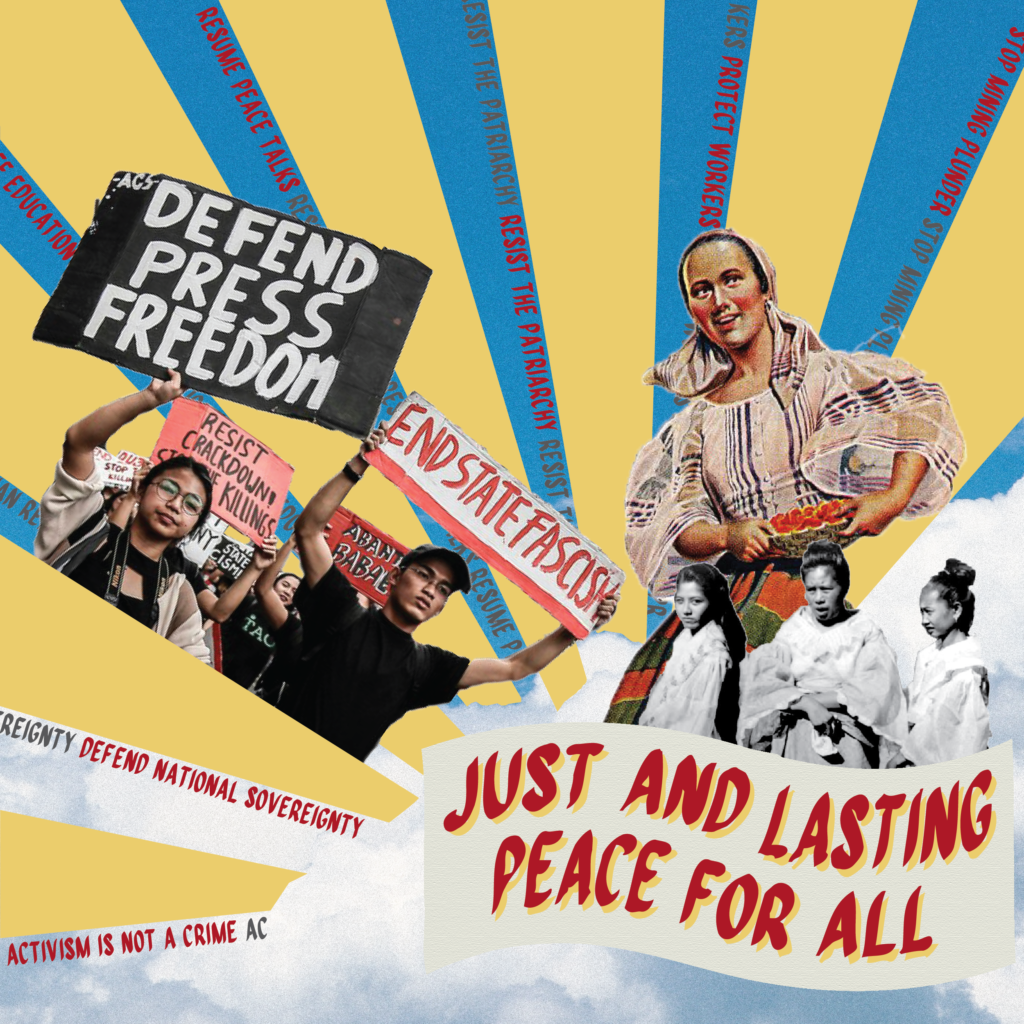

To me, peace is more than the absence of physical or direct violence. I want to see just and lasting peace for all. A just (in other words, fair) and lasting (in other words, sustainable) peace means we are addressing the root causes of conflict or violence in peacebuilding, not just the symptoms. And more often than not, the root causes are poverty and other social injustices.

We have seen that those in power control and manipulate the narrative of violence and terrorism to paint oppressed people as threats to peace, order and security. When we take a closer look, we find that they are actually demanding better social and economic conditions. The Philippine government, for example, regularly plants arms in the homes of human rights defenders (youth included) and then arrests them on trumped up charges. They have a history of calling activists ‘terrorists’, even making an anti-terror act to persecute them, when the reality is most of them are peasants and Indigenous people demanding better living conditions.

I see parallels in Canada with the federal government’s response to ongoing actions against the Coastal GasLink pipeline project through Wet’suwet’en territory. When the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs lawfully asserted their sovereignty in refusing the CGL, the federal government responded by sending the RCMP to crack down on them and solidarity actions across Canada. Who was really disturbing the peace here? If the answer is the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and their supporters, then ‘peacebuilding’ is actually just enforcing the status quo.

With all of these nuances in mind, I believe we should be working toward a just and lasting peace in Canada and abroad. How do we get there? Well, we need to be able to build peace on the personal, interpersonal (with our relationships and communities), and structural/systemic levels. Here’s a few ideas to start: nurturing our communities, and practicing compassion and empathy toward ourselves and our peers, centering women’s and other marginalized voices at formal peace-building tables, and making social policies that put people first.